Today we explore the basics of distillation and the physics of how we turn 7% alcohol by volume (abv) Apple cider into 70% abv, which is the strength at which we collect our brandy.

As an example, we will use our Newtown Pippin cider which fermented to 7.4% abv. The other 92.6% of the cider is mostly water.

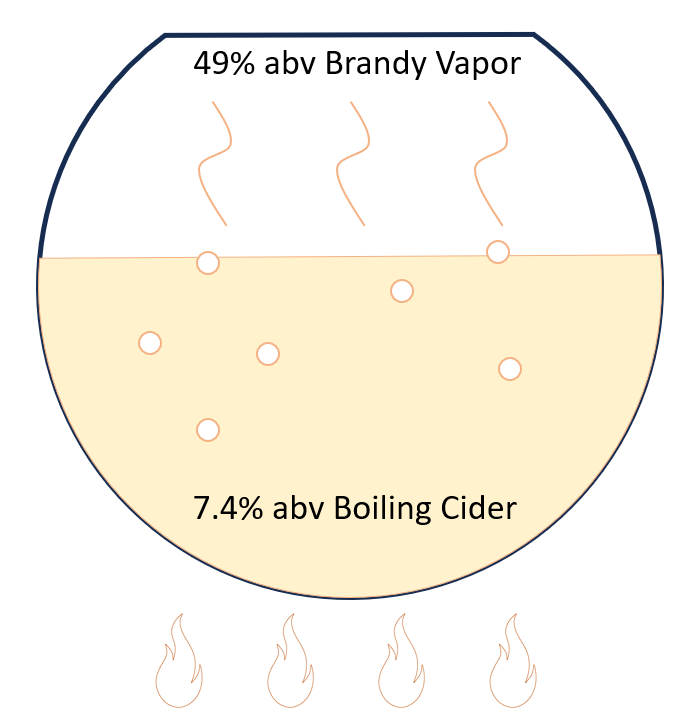

To distill the cider, we pour it into a pot and bring it to a boil. Water boils at 100 C (212 F), but ethanol boils at at a lower temperature of 78 C (173 F). Because our cider is mostly water with a few percent of ethanol, it boils at a bit less of a temperature than pure water in our example above at 95 C (202 F). At 95 C both ethanol and water vapors are being boiled out of the cider, but because ethanol has a lower boiling point it boils out more quickly than the water. When we boil our 7.4% alcohol cider the vapor is 49% alcohol – we have increased the alcohol by 7x just by boiling – then capturing the vapors in a condenser.

This is the key concept of distillation; boiling cider, wine, or beer will concentrate the alcohol in the vapors that come off, in this case turning 7.4% abv boiling cider into 49% abv vapors that we condense into brandy.

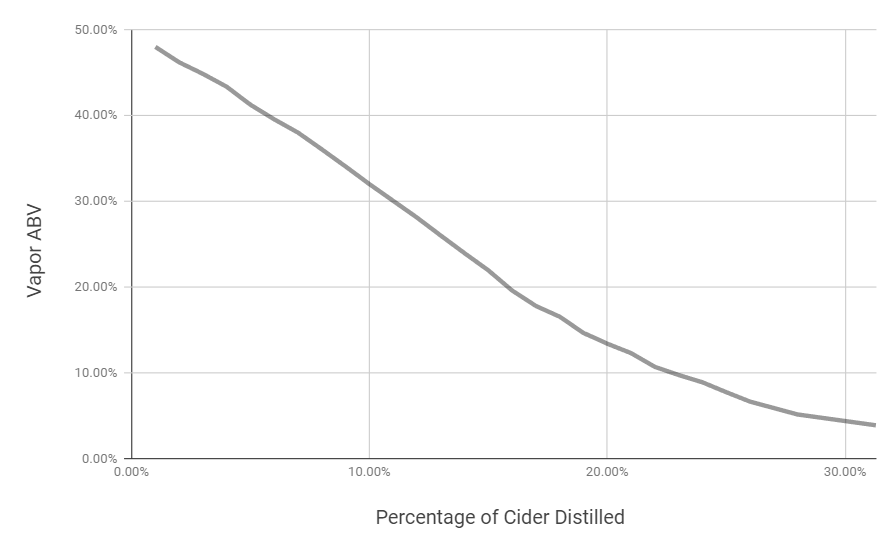

Because we are boiling off the alcohol out of the cider, what is left in the pot will start lowering in alcohol. After we have boiled off a tenth of the cider from the pot, what is left behind will now be less than 3.3% alcohol and as a result the vapor coming off will reduce in its purity to now be only 31% alcohol, and it keeps going down as we continue the process.

Because the alcohol level keeps reducing as we distill, once we’ve completed the distillation, in this example, we would have ended up with product that is only 22% abv alcohol; this is not strong enough or pure enough to make a great brandy. The challenge distillers face is how to produce brandy that is stronger and cleaner than simply boiling cider in a pot. This is where the art, science, and technique of distillation craft converge and life gets interesting.

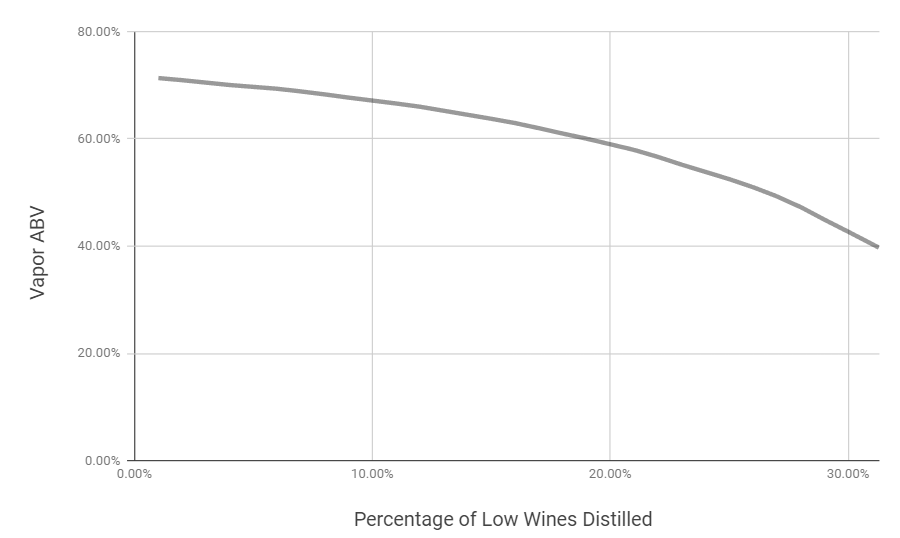

The easiest thing we can do is simply improve our technique and put the 22% abv single distilled weak-brandy, which is typically called Low Wines in English or Brouillis in French, back in the still and distill it a second time. Many traditional alembic distillers use this classic “Double Distillation” technique, including here at Ambix Spirits.

When we re-distill our 22% abv low wines the second time, it will boil at a lower temperature and the vapors will now come off at 71.5% abv. This is right in the sweet spot for making clean brandy that retains all the amazing flavor that was in the cider.

Of course the alcohol in the pot and vapors drop as we continue to boil it, just like the cider did. The brandy coming off starts tasting less clean once it gets down to 60% abv, after that point it is no longer good enough to go into the barrel and we stop our collection of product at that point.

So in our example, by double distilling our cider we will transform our 7.4% abv Newtown Pippin cider into clean 68% abv Newtown Pippin Brandy that is ready to be diluted with clean water and put into a barrel to age. In this process it takes about 18 gallons of cider to produce 1 gallon of brandy! This ratio is partially because of concentration, and partially because we will have only collected half of the alcohol into our barrel when we hit the 60% endpoint of the second distillation. The rest of the alcohol isn’t lost; we distill it and add it to our next distillation run, effectively distilling it a third time.

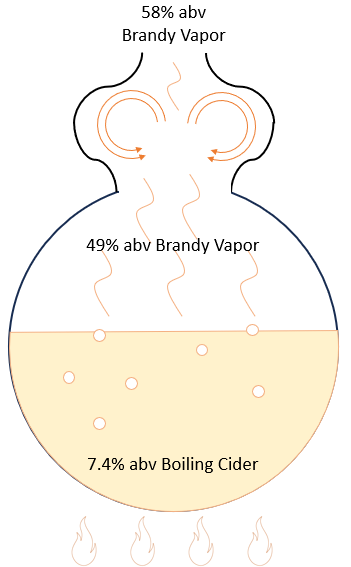

This technique of double distillation in a basic pot still is only one of many tools & tricks we use to make great brandy. Let’s also look at the art of the still itself. One of the most important elements of the alembic and a major impact on the flavor is the chapiteau, which is beautiful onion dome that is above our boiling pot

By adding the chapiteau, our still does much better for our Newtown Pippin run. We achieved ~58% from the cider, a 20% improvement in efficiency over what one would calculate for a simple pot still, and more importantly we concentrate the delicate flavors of the apples because of the shape of the chapiteau.

The shape of the chapiteau will cause a swirling vortex ring to form in our alembic, just like a a smoke ring can be blown. This swirling vortex of vapor causes some of the vapor that is coming up to swing out back down into the pot. When the vapor takes a lucky path right up the middle, it will make it through and be captured to make our brandy, but vapors that take an unlucky path towards the edge of the chapiteau will end up back in the pot. This is called reflux, which describes how some of the vapor gets caught by the vortex and has to try a second time to get out; this results in more efficient alcohol extraction and flavor concentration.

This intersection of the science of how alcohol and water boil differently, art of how every feature the still maker adds to the still to enhance the characteristics we are seeking in our brandy, and technique of how we use the still is what makes for the rich dialog that we enjoy participating in as craft distillation continues to evolve.